Lessons from Silicon Valley - What conservation planners can learn from the tech industry

Have you ever wondered why SECAS puts such a big emphasis on regularly updating the Blueprint and its associated online interfaces? It’s not easy, and it’s ambitious, but it comes from our commitment to following the Lean Startup method, an approach based on the book by entrepreneur Eric Ries. Lean Startup calls for moving quickly through the planning phase of a project, allowing for quick failure so teams can learn what works, what doesn’t, and what end users really need. Elements of this framework are more commonly used in the tech and manufacturing industries, so it might seem unusual to apply it to conservation. But, by thinking of the Blueprint and its viewers as products like any other—a phone, a car, an app—we’ve been able to incorporate key lessons.

Here are just some of the benefits we’ve seen from applying Lean Startup concepts to the Blueprint:

- It helps the Blueprint keep up with changing on-the-ground conditions and incorporate better data when it becomes available

- It helps build trust and promote user engagement by demonstrating a commitment to improving the Blueprint over time and taking feedback seriously

- It helps staff prioritize Blueprint improvements to focus on the needs of the people who actually use it day-in and day-out

- It helps avoid wasting staff time and resources on solutions that don’t work, or are a low priority for users

- It helps staff avoid getting bogged down in “what-if” scenarios and endless tinkering

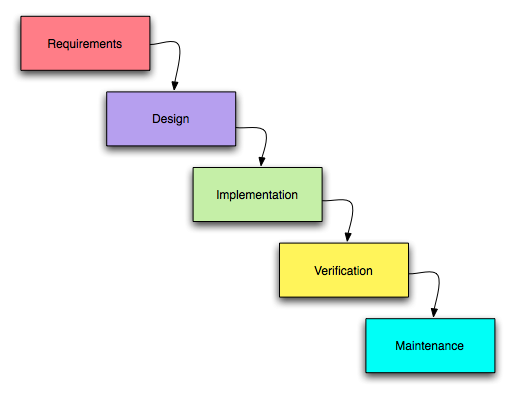

The traditional waterfall method

Lean Startup is an intentional departure from the traditional approach to product development, which is known as the waterfall method. In the waterfall method, a team tends to spend most of its time in the planning and development phase, do a little bit of testing to make sure the product works, and then move on the final release. One example might be a typical Master’s thesis—you develop your research question and approach, make a few adjustments based on feedback from your advisor and committee, implement your study design, collect your results, and try to publish.

One drawback to the waterfall method is that it’s really difficult to swim upstream. If a problem arises and you need to revise, going back to change the end product often requires a substantial amount of time and money. You might even discover that your final product doesn’t actually meet the needs of its users, but by the time you find out, it’s too expensive and time consuming to fix! For example, ask anyone who has earned a Master’s degree what they would have changed about their project, or what they would do differently next time—I bet they’ll have some ideas! But the system isn’t designed to provide those people an opportunity to adapt based on what they’ve learned (after all, no one wants to go back and redo their degree!).

Have you been part of a conservation planning exercise that uses the waterfall method? Many of us have! Did you ever have a sinking feeling that, by the time the priorities were ultimately identified, the window for the decision that you hoped the priorities would help inform might have already closed? Have you ever worked hard on a conservation plan only to find that it sat on a shelf, gathering dust, instead of being implemented? Have you ever relied heavily on a new innovative product or tool, only to find that it never got updated, and eventually it lost its relevance?

There is certainly a time and a place for the waterfall method, but we’ve found that employing Lean Startup in the development of the Blueprint can help avoid some of those potential pitfalls.

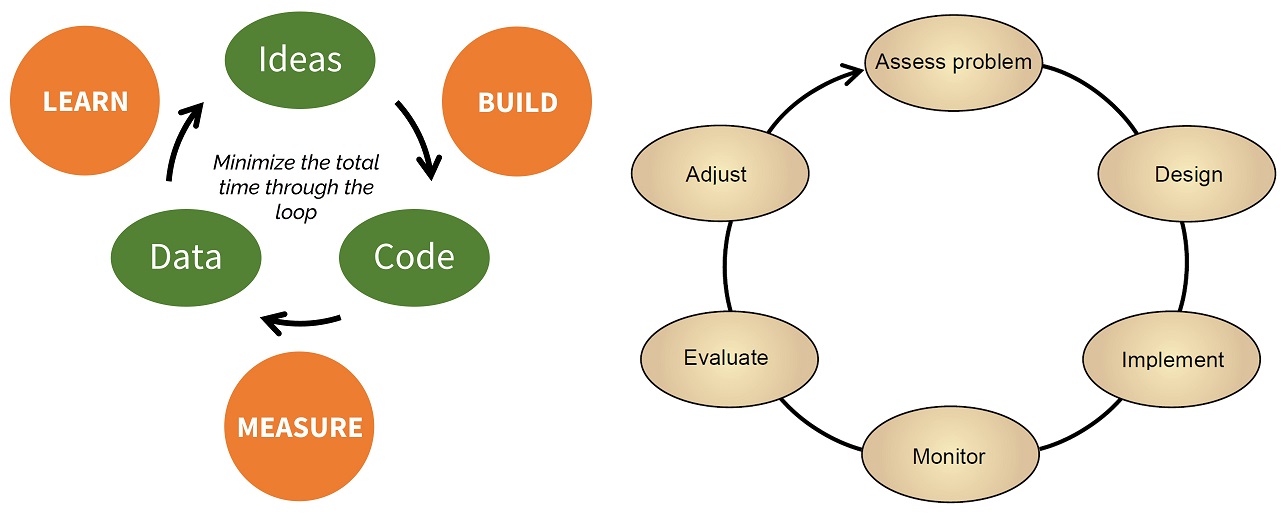

Lean Startup, aka “adaptive management on steroids”

In contrast to the waterfall method, Lean Startup minimizes the time spent in product development, and allocates most of a team’s resources to the revision process. Rather than waiting until the product is mostly complete to start testing and soliciting feedback, you start that process as soon as you put together what’s called a Minimum Viable Product—the simplest, cheapest version of a new product or feature that allows you to maximize learning. Lean Startup follows a cycle of iterative testing and revision called the “build, measure, learn” loop.

Does that seem familiar? It has a lot in common with the adaptive management cycle—so much, in fact, that SECAS staff sometimes fondly refer to it as “adaptive management on steroids” because of the unique emphasis on completing the loop efficiently.

You might have heard quotes like, “Fail early, fail often, but always fail forward” (John C. Maxwell) or, “Perfection is the enemy of progress” (Winston Churchill). That’s the basic idea here—accepting some imperfections in the service of learning can actually be the most direct path to success!

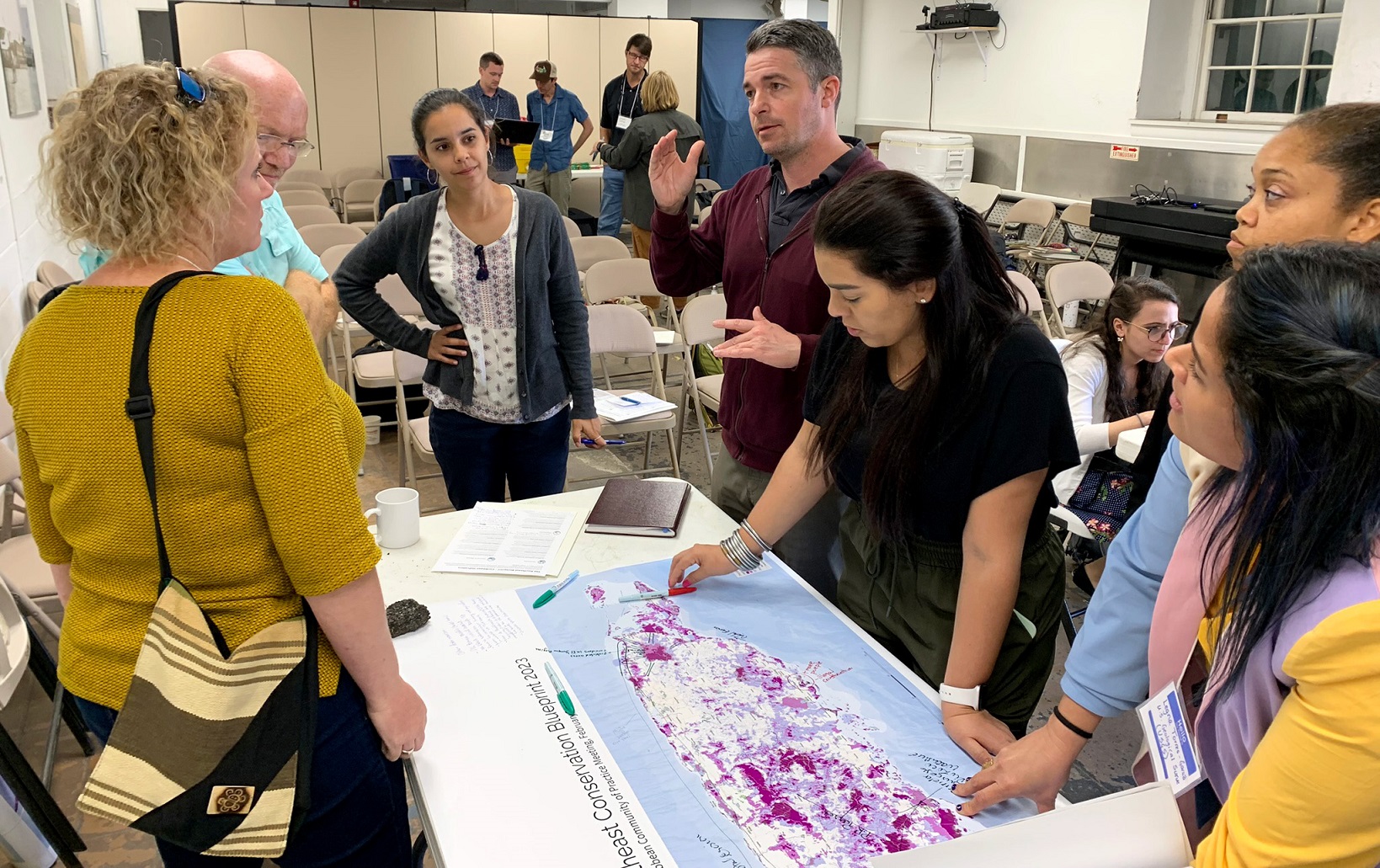

The fuel that powers the Blueprint revision cycle

Because the Blueprint’s end users come from the conservation community, feedback from folks like y’all is a major driver of the Blueprint revision cycle. In addition to collecting that input through Blueprint workshops and indicator teams, we rely on Blueprint users for insights. That’s why, if you work with Blueprint user support, you might hear us ask something like, “How well did the Blueprint meet your needs? Did you run into any issues? Is there anything we could change to make it more useful to you in the future?” We also track instances where folks tried to use the Blueprint, but couldn’t, to better understand any gaps or barriers.

We apply this same philosophy not only to the Blueprint priorities themselves, but to the online interfaces as well. We look to the fields of user experience, human-computer interaction, and user interface design for recommendations on designing and testing our viewers. Periodically, as we add or change features, we’ll do a new round of testing by observing a handful of folks as they use the viewers to complete a task. We watch where they click, listen as they narrate their thought process, and document where they run into pain points. These testing sessions are always full of lightbulb moments!

Throughout this process, our mantra is you are not your user. As staff, we’re way too close to the data and the viewers to be objective. Have you ever asked a colleague to proofread a document, found that they caught a bunch of obvious mistakes, and thought, “how on earth did I miss that?” While it’s tempting to imagine you can put yourself in someone else’s shoes and predict how they would react to an interface or interpret some wording, humans are notoriously bad at that! It’s always better to go straight to the source and gather real data from your target audience. It’s an easy trap to fall into, but one that can leave a team stuck in guesswork gridlock when testing with a few people could quickly reveal the most effective solution. This mindset has empowered us to abandon ideas that seemed promising in theory, but in testing turned out to cause more problems.

In addition to user feedback, the other factor that drives our regular Blueprint updates is the availability of new data. The landscape around us is changing all the time—seas are rising, marshes are migrating, grasslands are being restored, longleaf is being burned, dams are being removed, urban areas are growing. And meanwhile, the data we use to represent those conditions is changing, too! Without a process to keep up with that change, the Blueprint and indicators would become stale.

A guiding principle for SECAS

Lean Startup is just one of SECAS’s overall guiding principles, but it’s an important one. It overlaps with many different facets of how we work, including our focus on user support—and our commitment to transparency. If we’re embracing the concept that it’s better to release an imperfect plan than to fine-tune it in isolation, it becomes especially important to be transparent about those imperfections! That’s why we publish that long list of “known issues” with every version of the Blueprint. Blueprint user support staff are well-acquainted with those known issues and can help folks understand and think through the tradeoffs inherent in using the data. No dataset is perfect, and we often don’t need it to be in order to make a well-informed decision—but it’s still important to understand any shortcomings and their implications for a project.

If you’ve made it this far, I probably sound like a Lean Startup evangelist, and, well—I suppose I am. After working under this model for nearly a decade, I’m convinced! The Blueprint is much better today after 7 feedback-driven iterations than it would have been if we’d between working behind closed doors since 2015 to polish Version 1.0. And meanwhile, it’s been helping more than 350 people from over 140 organizations connect the lands and waters of the Southeast and achieve shared conservation goals.