The Southeast Blueprint helps inform local planning in the heart of the Southern megalopolis

In the conservation world, we often think of urban growth as a threat, a stressor, a driver of land-use change. And it undoubtedly is. But that expanding urban frontier also represents an opportunity to work with communities who want to grow sustainably, protect their natural resources, and ensure their residents have access to green space.

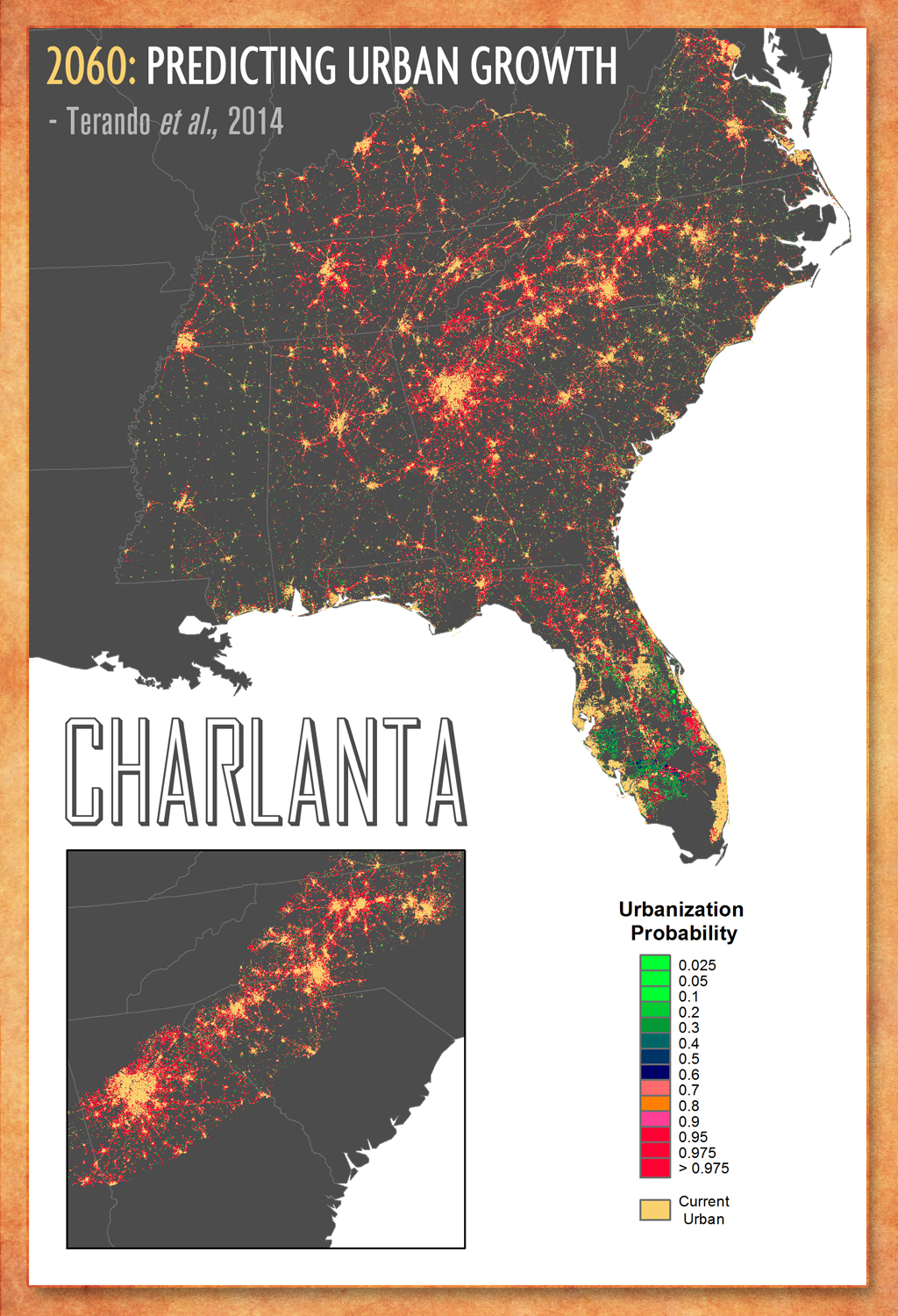

The predicted emergence of the Southern megalopolis really illustrated the magnitude of urbanization we’re facing in our region, with its map of “Charlanta”, a giant city linking Charlotte, NC to Atlanta, GA along the I-85 corridor. Based on more recent real estate and development trends, urbanization is showing no signs of losing its momentum, even during the pandemic. So how does Charlanta fit into the ecologically connected network of lands and waters called for in the SECAS vision? How can SECAS confront this challenge and seize the corresponding opportunity to plan for a future that leaves room for people and critters and ecosystems and everything in between?

In my view, we do that by helping both conservation and planning professionals alike use the Blueprint. The Blueprint doesn’t stop at the city limits—it identifies important places in and around growing urban communities that have significant natural and cultural resource values. Back in 2015, the South Atlantic Blueprint team held a series of workshops to review the latest draft of the South Atlantic Blueprint (one of the inputs to the Southeast Blueprint). We looked at Blueprint priority areas that were predicted to change due to urban growth and sea-level rise and asked folks where they wanted to work. Did they want to continue working in these rapidly changing areas, or take a lower-risk approach and avoid them? 82% of workshop participants wanted to continue working in areas likely to develop or become inundated. And since it appears most folks are comfortable operating in the intersection of conservation priority and land-use change—well, it’s our job to make sure the Blueprint is, too.

But how can a big, regional plan like the Blueprint make a meaningful difference at the local level? How can the Blueprint shape the conservation landscape of the future within urban communities? I hear variations on that question a lot. It’s a great question, and we’ve thought a lot about it—the South Atlantic Blueprint team even worked with the American Planning Association (APA) to dig into that topic several years ago. The APA team made several recommendations on how to better integrate the Blueprint into local planning, as well as indicator improvements to better capture priorities within urban areas. The greenways and trails indicator is an example of one of the suggestions that we’ve already implemented.

For the last couple of years, we’ve been working with urban communities and learning about the role the Blueprint can play in local planning. The Blueprint has been used as a resource by communities and partnerships in NC, SC, and FL to depict conservation priorities, plan for growth, and guide land protection efforts.

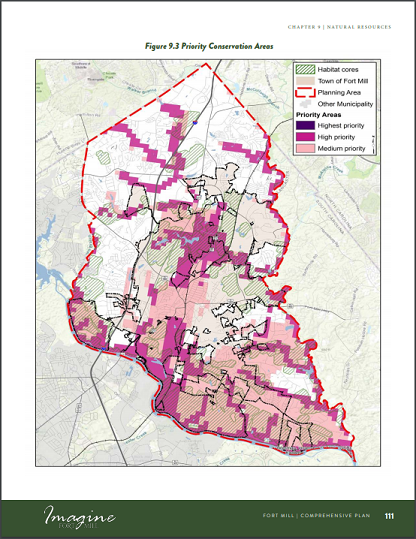

One of the most exciting recent examples of how the Blueprint is informing conservation within growing urban communities takes place in the heart of the Southern megalopolis, just south of Charlotte across the SC state line. The Catawba Council of Government, representing Chester, Lancaster, Union, and York counties, is working with city and county governments within upstate SC to incorporate the Blueprint into their comprehensive plans. The Town of Fort Mill, SC recently adopted its 2040 comprehensive plan, which used the Blueprint to help identify natural resource priorities. Fort Mill will use the natural resource priorities to guide efforts to conserve key habitat, expand outdoor recreation opportunities, inform future land use planning, and mitigate the impacts of development. The Blueprint and underlying indicators also helped recommend conservation actions to undertake within these focus areas, such as promoting connectivity, restoring Piedmont prairie plants and pollinators, controlling invasive species, restoring riparian buffers, and removing aquatic barriers.

One of the most exciting recent examples of how the Blueprint is informing conservation within growing urban communities takes place in the heart of the Southern megalopolis, just south of Charlotte across the SC state line. The Catawba Council of Government, representing Chester, Lancaster, Union, and York counties, is working with city and county governments within upstate SC to incorporate the Blueprint into their comprehensive plans. The Town of Fort Mill, SC recently adopted its 2040 comprehensive plan, which used the Blueprint to help identify natural resource priorities. Fort Mill will use the natural resource priorities to guide efforts to conserve key habitat, expand outdoor recreation opportunities, inform future land use planning, and mitigate the impacts of development. The Blueprint and underlying indicators also helped recommend conservation actions to undertake within these focus areas, such as promoting connectivity, restoring Piedmont prairie plants and pollinators, controlling invasive species, restoring riparian buffers, and removing aquatic barriers.

We’re continuing our collaboration with the Catawba Council of Government on several other local plans in upstate SC, which are working their way through various stages of revision and approval by elected officials. To me, this shows how the Blueprint can help align local actions with a regional strategy. This becomes even more powerful when other organizations are also aligning with that same strategy! That’s what a plan for shared action is all about.

If we don’t coordinate around a common strategy, we may miss our chance to create a connected network of lands and waters that accounts for urbanization and other threats. Charlanta isn’t going to happen overnight. It’s one potential future, a product of thousands of underlying decisions and plans that we have the ability to shape. If we can work together to plug the Blueprint into many of those decision points, we can create a different future.

In South Carolina, alignment with the Blueprint is already underway at multiple scales, from federal, to state, to local. A wide range of organizations have already used–or are in the process of using–the Blueprint to inform their work, including:

- The Conservation Bank, through its priority mapping

- The Nature Conservancy, through its statewide conservation vision

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, through Refuge Landscape Conservation Designs and other planning documents (like this LCD for the Central Coastal Plain)

- The U.S. Forest Service, through its 2018 Land Ownership Adjustment Strategy

- The Department of Natural Resources, through upcoming updates to its State Wildlife Action Plan

- The Forestry Commission, through upcoming updates to its Forest Action Plan

- The Upper Waccamaw Task Force, through its emerging land acquisition strategy

In addition to these planning and prioritization efforts, many of those organizations are also using the Blueprint to bring in new funding for land protection and restoration. Now that city and county governments are incorporating the Blueprint into their local planning efforts, too—well, that’s where the magic happens. When I consider the collective passion and resources of all those people collaborating around common priorities, a connected network of lands and waters really starts to feel achievable, despite the threats we’re facing.