Sentinel Landscapes - Landscape-level collaborative conservation

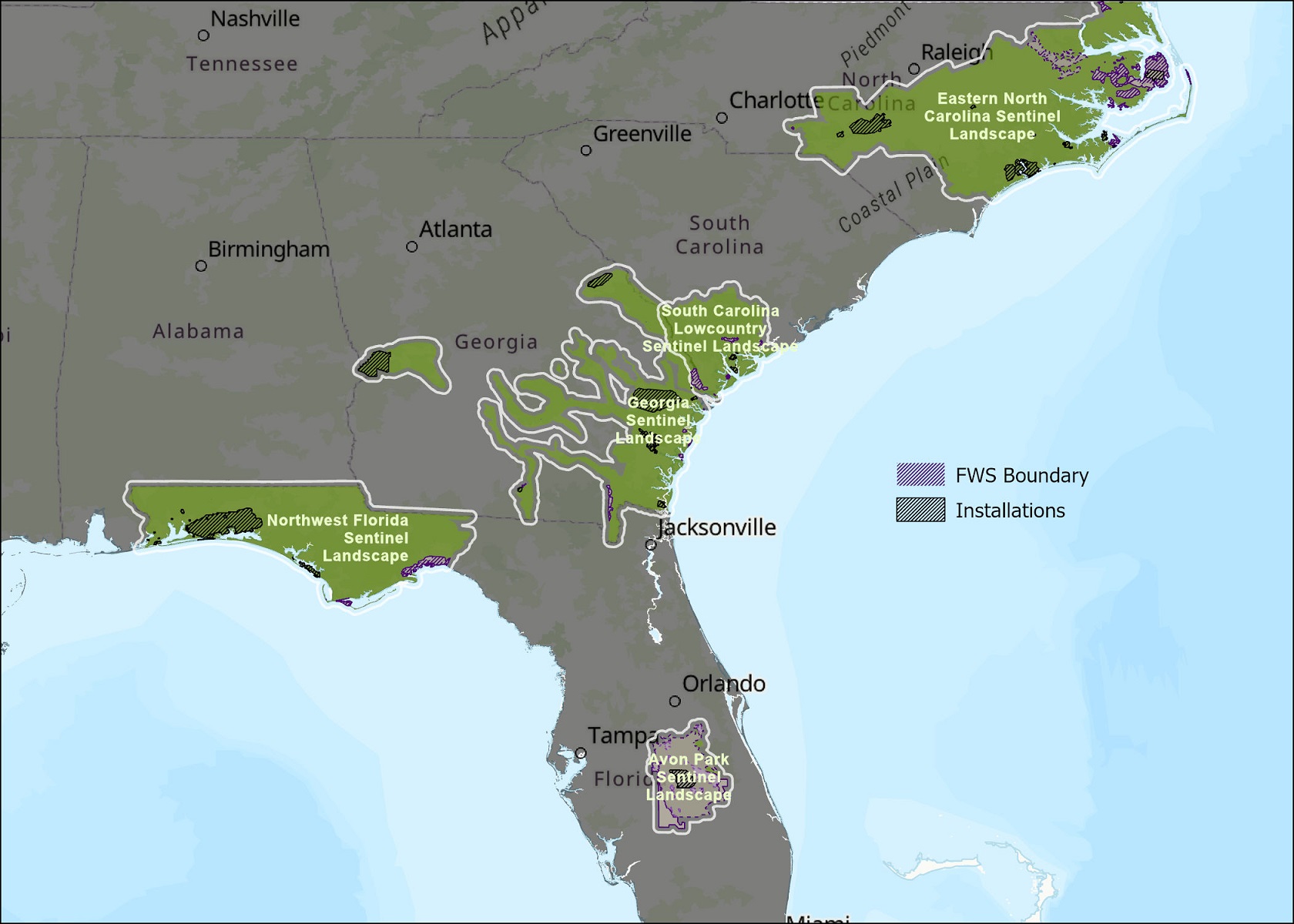

As of May 2024, there are 18 landscapes across the United States designated as Sentinel Landscapes Partnerships. Five of these Sentinel Landscapes (SLs) are within the Southeast region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS): Eastern North Carolina SL, South Carolina Lowcountry SL, Georgia SL, Northwest Florida SL, and the Avon Park Air Force Range SL in Florida. Another two (Camp Bullis SL in Texas and the Virginia Security Corridor SL) fall in other parts of the SECAS geography within other U.S. FWS regions. But what is a Sentinel Landscape? How are areas with this designation different from other conservation areas? And how can the U.S. FWS work with other partners within these landscapes to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people?

This summer, as a U.S. FWS Directorate Fellow, I’ve been working on those questions and meeting with the SL Coordinators and other major partners in Southeast conservation. My focus has been on how the FWS can best support, contribute to, and benefit from Sentinel Landscapes Partnerships, but these benefits extend to everyone hoping to make an impact on landscape-level conservation within these areas—which definitely includes the SECAS community.

Understanding the Designation

Sentinel Landscapes are geographically defined areas that contain at least one high-value military installation or range, as well as high-priority lands for conservation, working lands, and national defense interests. They also face unique challenges in managing their lands for conservation since training exercises can often be disruptive and damaging to the species and people who live nearby.

The Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration (REPI) program was created to help assist in managing lands directly surrounding installations. But urban development has continued to obstruct air space, encroach on buffers, and put pressure on the species living in the areas around military installations. Habitat loss has forced many species to find refuge in the habitat that remains on military lands. The presence of at-risk, threatened, and endangered species has repeatedly limited or halted testing and training in those areas. As a result, the national defense community has a strong interest in sustaining natural and working lands so they are able to continue meeting their primary mission. Sentinel Landscapes help achieve this by facilitating partnerships, making key areas more competitive for federal funding, and connecting landowners with programs to keep lands undeveloped (e.g., voluntary tax reduction programs, agricultural loans, technical aid, conservation easements).

Defining Common Priorities

The Sentinel Landscapes Partnership organized a broader set of conservation-minded organizations at the same table to address common concerns: habitat for imperiled species, maintaining working lands, protecting water resources, reducing urban encroachment, and managing towards climate resilience.

Tools like the Southeast Conservation Blueprint have been used to help identify and justify Sentinel Landscape boundaries and conservation goals. The Landscapes are focused on ecosystem conservation by creating a network connected habitats, which is a key element of the Southeast Conservation Blueprint approach. As a result, Sentinel Landscapes can be used as a mechanism for identifying important areas for conservation that will have a local (immediate) impact, as well as landscape (long-term) impact.

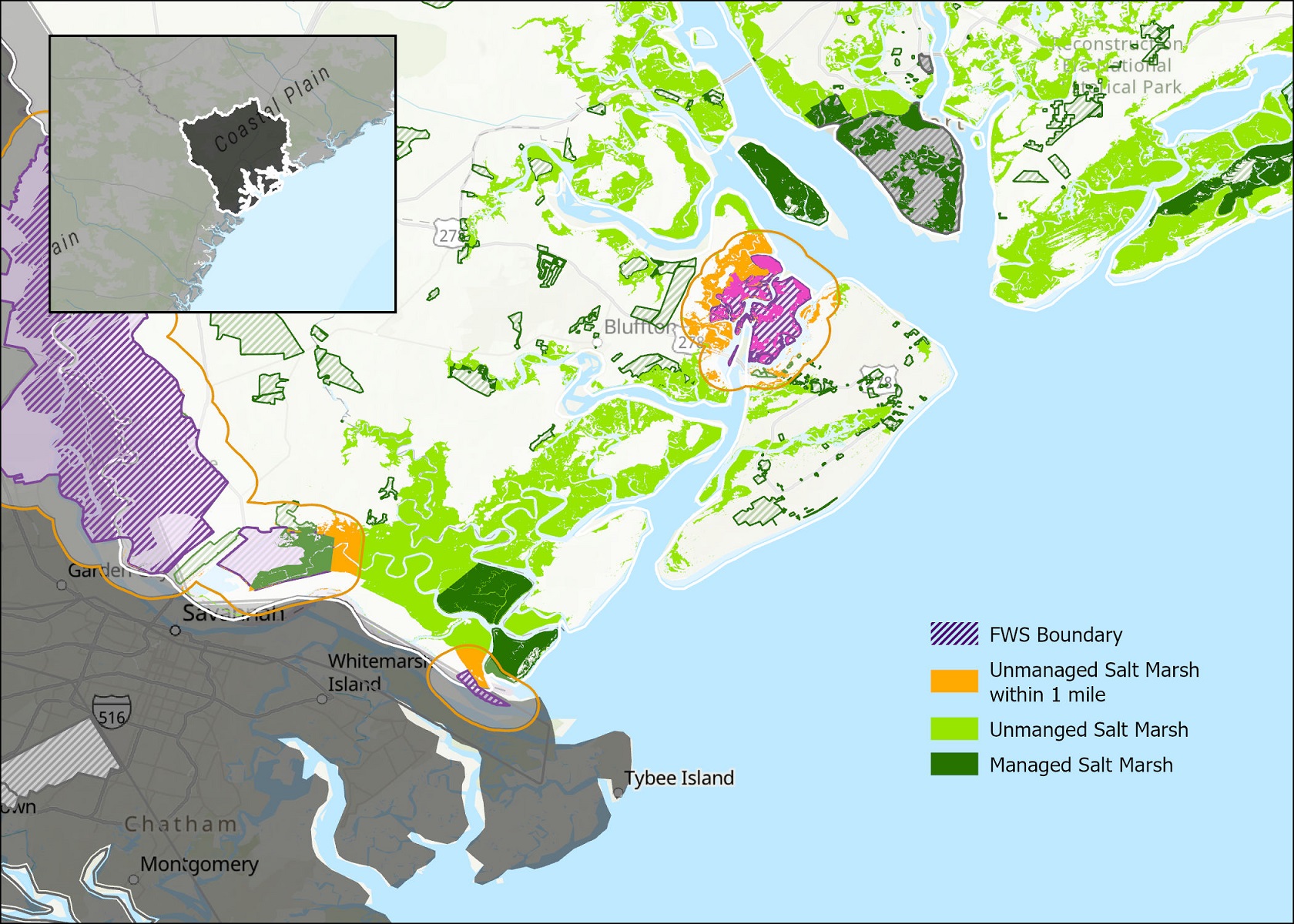

For example, salt marshes are a crucial habitat for many species along the Atlantic coast and help to protect the shoreline and infrastructure from intense storms. However, salt marsh is threatened by sea-level rise, urbanization, and habitat fragmentation. The 2023 Recent trends in Southeastern ecosystems report shows that salt marsh area is declining regionwide, making it off-track to achieve the SECAS Goal of a 10% or greater improvement by 2060; in addition, achieving “no net loss” of the benefits provided by salt marsh is the core goal of the South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative.

Along the South Atlantic coast, three Sentinel Landscapes support nearly 625,000 acres of salt marsh, making them well-positioned to contribute to these regional objectives. While the U.S. FWS manages about 8% of that salt marsh through the National Wildlife Refuge System, over half of the salt marsh within those Sentinel Landscapes is not currently protected by any national, state, local, or non-governmental group. How can the FWS better work with partners within Sentinel Landscapes to enhance and sustain a functional network of salt marsh habitat along the South Atlantic coast?

There are currently 14,000 acres of salt marsh within one mile of existing U.S. FWS Refuges. But protecting all of these lands is challenging—if not impossible—without greater collaboration across organizations.

Collaboration is the Benefit

Sentinel Landscapes represent areas where federal, state, and local organizations have formalized their shared commitment to collaborative conservation. These partnerships make it easier to leverage existing knowledge, resources, and people towards increased on-the-ground actions and funding opportunities in these defined geographies. Communities of conservation mean less work for each individual involved. I have really grown to appreciate the role that Sentinel Landscapes are playing in elevating a landscape-level conservation perspective. Groups that have a narrow conservation focus, such as protecting a single species, can still know that their work is building towards a larger goal. In Sentinel Landscapes, there is something for everyone.

This idea fits in directly with the vision of the FWS, which “envision[s] a future where people and nature thrive in an interconnected way and where every community feels part of and committed to the natural world around us.” It also evokes the SECAS vision of a “a connected network of lands and waters that supports thriving fish and wildlife populations and improved quality of life for people.”

Knowing that Sentinel Landscapes exist is the first step. Identifying that you are within a Sentinel Landscape is next. But finding out what work is currently happening within the Sentinel Landscape, and how to get connected and encourage that conservation, is the most important!

To learn more about the Sentinel Landscapes near you, visit sentinellandscapes.org.