Southeast CASC Project Spotlight - Working together towards a conservation landscape of the future

Hidden Paradise

Fall has just started in Umstead State Park. Turtles bask on logs to ward off the morning chill. Sunlight dapples an already-thick cushion of leaves that dampens hikers’ footsteps. Chickadees sing about cheeseburgers in red-tipped trees while bees buzz around late-blooming asters. The air vibrates with calm, quiet life.

It’s easy to forget that the park sits in the middle of one of the fastest growing communities in the nation.

William B. Umstead State Park is located 10 miles northwest of downtown Raleigh, North Carolina. Visitors enjoy over 30 miles of hiking and multi-use trails, camping, and fishing and boating at three manmade lakes. The park is one of the largest protected habitats in Wake County and is home to more than 145 bird species and 800 species of plants.

Wake County makes up one corner of North Carolina’s “Research Triangle”, the cluster of cities that house the three largest research universities in the state. Raleigh, the state’s capital, and the surrounding communities within Wake County are home to nearly a million people. The area is booming; on average, 40 new people move here each day, a total of 250,000 new residents in the last ten years.

While this growth creates new economic opportunities, it comes with a cost to natural areas. Wake County loses the equivalent of Umstead State Park (5,600 acres) to development every two years.

“The Southeast is a very rapidly growing region,” says Adam Terando, Research Ecologist for the USGS Southeast Climate Adaptation Science Center (Southeast CASC). “And we tend to build out instead of up, creating sprawling urban centers with a lot of barriers to wildlife movement.”

Warnings of Unchecked Growth

Terando is acutely aware of the environmental and social challenges that come with urban growth. During his stint on the Raleigh City Planning Commission, he listened to citizens concerned by historical redlining and unequal access to public parks and transportation. He watched proposed highway expansions come and go, as reduced commute times were outweighed by the needs of displaced families and business.

At the same time, he spent his day job with the USGS meeting with natural resource managers and conservation practitioners, where everyone had two things on their mind: climate change and land development. How can they manage their lands and species when everything around them is changing?

Combining his city planning and scientific interests, Terando developed a collaboration between USGS and North Carolina State University (NCSU) researchers to explore urbanization patterns in the Southeast. Using data from the USGS National Land Cover Database (NLCD), they developed a model to describe patterns of urban and suburban developments. They then applied computational resources at NCSU to simulate these patterns in the future, creating visualizations of what cities in the Southeast could look like in the latter half of the century.

“What might urban growth look like in the future? What areas are going to be most susceptible?”

The results were clear.

“If we continue to develop urban areas in the Southeast the way we have for the past 60 years, we can expect natural areas will become increasingly fragmented,” Terando says. “We could be looking at a seamless corridor of urban development running from Raleigh to Atlanta, and possibly as far as Birmingham, within the next 50 years.”

The study suggests that urban land use in the Southeast could nearly double by 2060, destroying and disconnecting some of the nation’s most biologically diverse ecosystems. Follow-up studies suggest bleak prognoses for sensitive species, such as freshwater fish and macroinvertebrates.

To preserve their iconic landscapes, to allow their communities and ecosystems to thrive side-by-side, the South was going to have to get creative.

A Conservation Landscape of the Future

“By and large, conservation inherits the leftovers,” says Bill Uihlein, Assistant Regional Director of the USFWS Science Applications and Migratory Birds Programs. “Everybody comes in, you change the land to asphalt, and what’s left over is what’s for conservation.”

“But what if that wasn’t true? What if, instead of getting the leftovers, we defined what’s needed to sustain fish, wildlife, and plants, and then worked together towards that goal?”

The USFWS is a major player in conserving and managing wildlife in the Southeast. Through the Southeast Science Applications Program, USFWS invests significant funding and staff support in a regional partnership called the Southeast Conservation Adaptation Strategy (SECAS). SECAS brings together state and federal agencies, nonprofit organizations, private landowners and businesses, Tribal Nations, and universities to work towards a shared goal of improving the health, function, and connectivity of southeastern ecosystems by 10% by 2060.

“SECAS is about defining the conservation landscape for the future.”

SECAS was immediately interested in Terando’s urbanization models.

“I was modeling things that I thought were important for understanding the broader risk posed by global change, and SECAS cared about how these changes affect managers’ abilities to do their jobs,” Terando says. “It became a really close collaboration.”

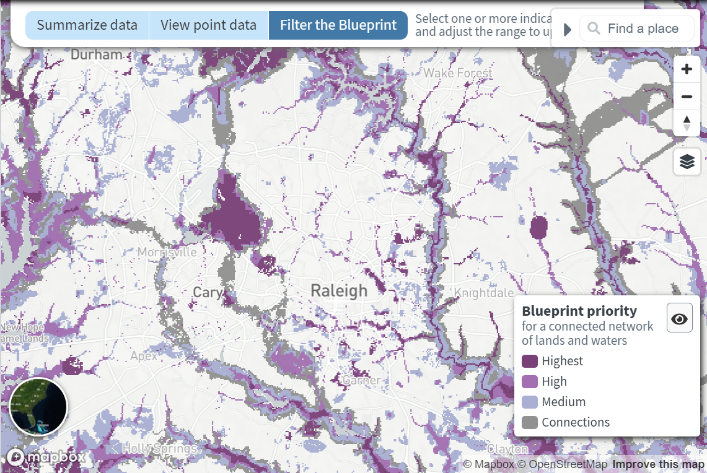

The models were one of the first threat layers available to overlay with the Southeast Conservation Blueprint, SECAS’s primary conservation tool. The Blueprint is a living, interactive map of the Southeast and U.S. Caribbean that identifies priority areas for a connected network of lands and waters. Through online viewers and the support of staff dedicated to helping people use and interpret the data, users can filter the Blueprint priorities to find their piece of this larger strategy. That can include the part of the Blueprint that’s most resilient to sea-level rise impacts, the part that best contributes to wildlife corridors, the part where riparian buffer restoration would most benefit forest birds, and more.

SECAS works not only for the benefit of fish and wildlife, but also for thriving human communities. Ensuring equitable access to outdoor recreation, productive working lands, and healthy populations of culturally significant species are all key parts of the partnership’s vision. As a result, the Blueprint recognizes the conservation value of different land uses, from large swaths of untouched land to urban green spaces. For example, the Blueprint categorizes both Umstead State Park and urban greenways cutting through North Raleigh suburbs as “Highest Priority” areas, albeit for different reasons.

This broad conservation approach is unconventional.

“Many decision support tools are defined by individual resources, like waterfowl or fisheries,” says Uihlein. “But the Southeast Blueprint tries to look across all the different natural and cultural resources and build a picture of what they look like collectively.”

A critical filter to put the Blueprint into the context of a changing landscape: the threat of urbanization. The Blueprint viewers and user support staff can help users to see how likely an area is to become developed in the next 40 years, based on Terando’s urbanization models and the next generation of new urban growth forecasts.

“Our users want to know how the projects they’re working on are likely to be impacted by urbanization,” says Hilary Morris, SECAS Blueprint User Support & Communications Specialist. “Sometimes it can help them make a case for the urgency of the actions they’re proposing.”

To date, the Blueprint has been used by more than 350 people from over 140 organizations across the Southeast to bring in new funding and inform conservation and planning decisions. For example, Morris and Terando traveled together to give a presentation to Ten at the Top, a community organization of ten counties in upstate South Carolina.

“It’s a group that’s working to ensure that the Upstate is developing in a sustainable way that enriches rather than degrades the quality of life for residents,” says Morris. “Adam [Terando] walked them through the urbanization data, showing that their area was growing really rapidly, and I talked to them about how the Blueprint can help them achieve their sustainability goals.”

The focus on user support from SECAS staff like Morris is a unique, and critical, aspect of the Blueprint.

“We’ve found that if you want people to use your tool, you need to be ready to help them use it, to provide that added capacity and help with interpretation,” says Morris. “And you should be committed to improving it over time, because as the landscape around us changes and new data becomes available, your product can quickly become out of date and lose its relevance.”

“We’re really committed to that testing and revision process and really helping our users implement the Blueprint.”

Longstanding Partnerships

Terando’s collaboration with SECAS exemplifies how the Climate Adaptation Science Centers work together with the USFWS Science Applications Program.

“I can tell you that the success of the SECAS partnership and the development of the Blueprint wouldn’t have happened without the Southeast CASC,” says Uihlein. “It doesn’t work if you don’t have those amazing people who are willing and interested in working together.”

CASC researchers, like Terando, provide scientific expertise that the Science Applications Program doesn’t have, particularly around climate and global change. In turn, the USFWS gives the CASCs a “seat at the table” of conservation conversations, providing a window into the needs of managers and practitioners that the CASCs use to improve their science.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service has the standing to convene discussions between federal and state agencies, non-profits, and even local organizations,” says Southeast CASC Assistant Regional Administrator Ryan Boyles. “We are often in the room listening, trying to understand the nature of the challenge, and how the science is going to get used.”

“It really gives us a better understanding of what science is needed to support some of these key agencies we’re charged with supporting.”

The Southeast CASC and SECAS have worked together for a long time, almost as long as both programs have existed. Their staff have served on each other’s external review boards, attended each other’s symposiums and meetings, and collaborated on a number of projects.

“We are both young programs, we are both evolving,” says Boyles. “The nice thing is that I feel like we’re evolving together. And because there’s such close communication, we have a sense of where each other is going and can help each other grow in a way that benefits everyone.”

Moving Forward

More than ten years after the first effort, Terando and his NCSU collaborators are still developing new and updated urbanization models. They work closely with SECAS staff to incorporate updates into the Blueprint viewers.

This experience has driven home for him the important role cities play in the conservation landscape.

“If you care about things like climate change and conservation, then cities are going to be a really important part of the solution to that,” he says. “And you are really seeing cities, like Raleigh, think much more carefully about building up and not just out, creating green spaces, incorporating public transportation – things that will really create a more sustainable future.”

For its part, Raleigh is halfway through its 2030 comprehensive development plan based on the three pillars of social, economic, and environmental sustainability. Part of this plan involves expanding the greenway system, a key recreational resource that’s included in the Blueprint. The city has also joined the U.S. Mayors Climate Protection Agreement to reduce its carbon footprint.

And Umstead State Park remains a wildlife paradise nestled in a (thoughtfully!) growing metropolis.