From the archive - Identifying ambitious but achievable ecosystem goals for the Southeast

Setting goals for the future is hard. It never feels like we have enough data and the future is so uncertain. That said, goals can be a powerful way to bring in new resources and stay focused on outcomes. A couple of months ago, I talked about assessing the state of the Southeastern ecosystems. This month’s post will be about some data being used to identify an ambitious but achievable goal for Southeastern ecosystems.

A major focus for the Southeast Conservation Adaptation Strategy (SECAS) this year has been to identify an explicit long-term and near-term goal. That leads to a big question: What’s possible in the Southeast?

Past changes can give us a good sense of what could be possible in the future. There aren’t a ton of places where we have long-term data from ecosystem indicators. Where we do, it’s a mix of good news and bad news.

Forests

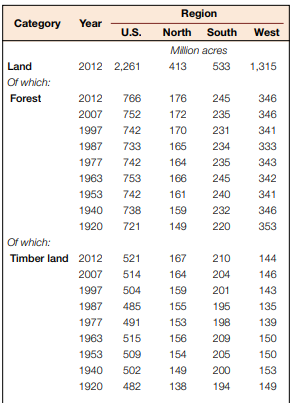

Forest area has been increasing over the last few decades. The table below is based on Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data. If you look at the “South” column, you’ll see an increase in both forest and timber land area. You’ll also notice that the area of forest and timber land is now as large or larger than in any other decade since 1920.

The news for forests, of course, isn’t all good. The 2016 report on the Future of America’s Forests and Rangelands by the U.S. Forest Service says that, while forest area has been increasing, so has the amount of fragmentation of forests overall.

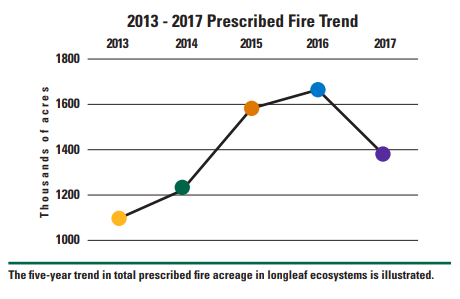

Despite a tough year for fire in 2017, prescribed fire in longleaf was still greater than it was 4 to 5 years ago. The focus on longleaf is resulting in more longleaf acres and increased longleaf management. You might remember I mentioned in my previous blog that pine and prairie birds are still declining, according to the Breeding Bird Survey. Those analyses only went to 2015, and it can take a while for species to respond to habitat improvements. It’ll be interesting to see if we start seeing changes in the trends for a number of longleaf bird species in the near future.

Watersheds

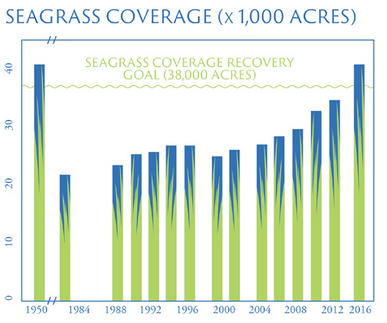

It seems like even in watersheds seeing large increases in human population, improvements are still possible. In that previous post, I mentioned the improvements in the Chesapeake Bay despite a 34% percent increase in population within that watershed. Here’s another example from Tampa Bay in Florida. Despite a huge amount of population growth in that area, they were still able to get seagrass coverage back to where it was in the 50s. Back in 1950, Hillsborough County, one of the three counties draining into the bay, had around 248,000 people. In 2017, they had 1.4 million.

Conclusion

There are certainly big challenges ahead, but it seems like improvements in many Southeastern ecosystems are possible—even with the huge population growth we’re seeing!